Talk Overview

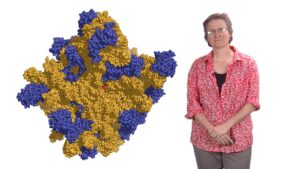

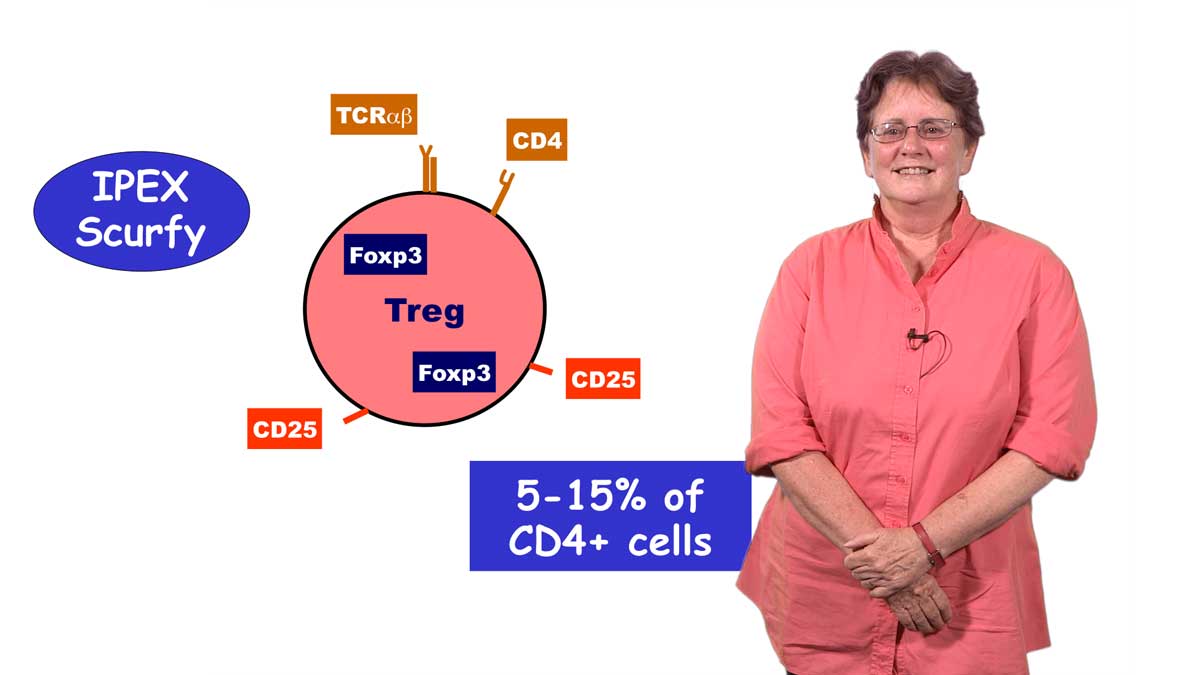

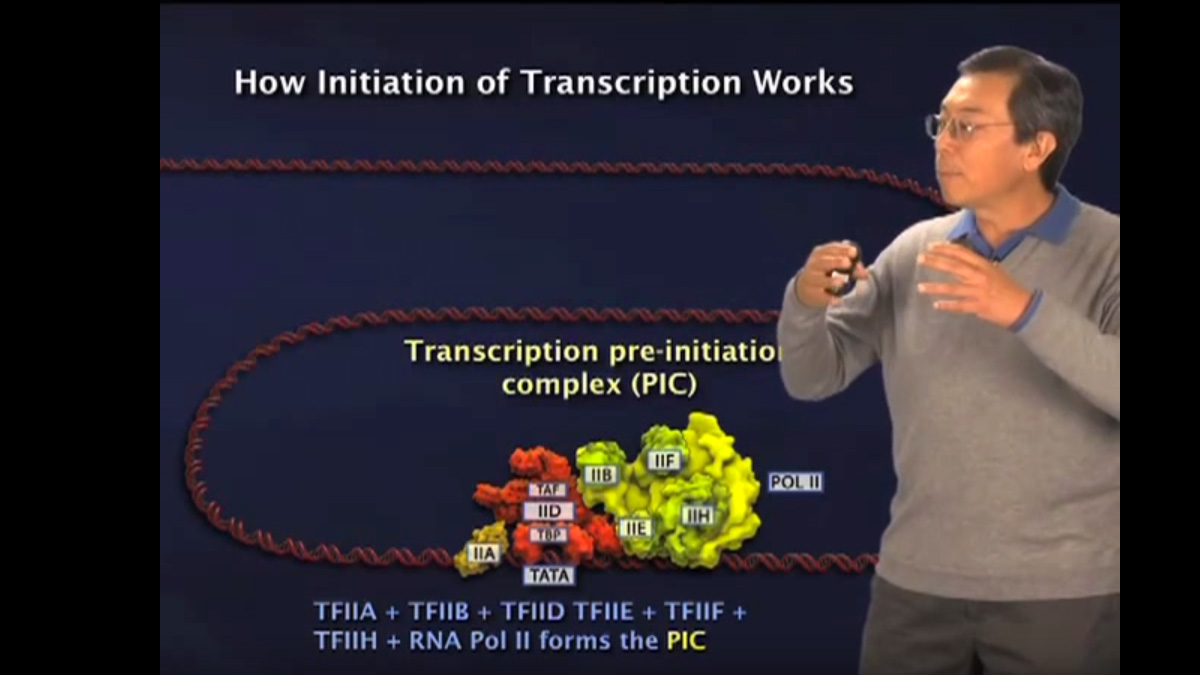

In her first talk, Green provides a detailed look at protein synthesis, or translation. Translation is the process by which nucleotides, the “language” of DNA and RNA, are translated into amino acids, the “language” of proteins. Green begins by describing the components needed for protein synthesis; mRNA, tRNA, ribosomes, and the initiation, elongation, and termination factors. She then explains the roles of these players in ensuring accuracy during the initiation, elongation, termination and recycling steps of the translation process. By comparing protein synthesis in bacteria and eukaryotes, Green explains that it is possible to determine which components and steps are highly conserved and predate the divergence of different kingdoms on the tree of life, and which are more recent adaptations.

Green’s second talk focuses on work from her lab investigating how ribosomes detect defective mRNAs and trigger events leading to the degradation of the bad RNA and the incompletely translated protein product and to the recycling of the ribosome components. Working in yeast and using a number of biochemical and genetic techniques, Green’s lab showed that the protein Dom34 is critical for facilitating ribosome release from the short mRNAs that result from mRNA cleavage. Experiments showed that Dom34-mediated rescue of ribosomes from short mRNAs is an essential process for cell survival in higher eukaryotes.

Speaker Bio

Rachel Green

Rachel Green received her BS in chemistry from the University of Michigan. She then moved to Harvard to pursue her PhD in the lab of Jack Szostak where she worked on designing catalytic RNA molecules and investigating their implications for the evolution of life. As a post-doctoral fellow at the University of California, Santa Cruz,… Continue Reading

Daniel Hunt says

I would like to ask a question pertaining to the GGQ motif and your elusion to significant differences in protein structure differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms that point to convergent evolution for these highly conserved processes.

Can this be exploited in vaccine development? Rather than developing vaccines that lose antibody efficacy after a few months, a conserved process could be targeted for longer lasting vaccines right?

I’m wondering your thoughts and if there’s research or other material regarding this? If I’m wrong I’d appreciate being set right about this, and thank you for the great lecture!!

Thanks